Sunday, October 17, 2021

What Happened on Highway 61? - Part 5: Memphis, City of Kings and Conquerors

Thursday, September 30, 2021

What happened on Highway 61? - Part 4: White Castles and the Camino to Liberty.

* Adherence to Habeus Corpus

made Slavery illegal under English Law. Trade in Slaves made illegal 1807 and

finally, in 1833 abolished in the British Empire. The latter, resulting in no

small part by the Abolitionists and not least for economic considerations. In

our system, a much cheaper, more efficient system existed. That of a kind of

indentured and child labor, which together with machination might easily be

be seen today, as enslavement. To secure abolishment, the Slave Compensation

Act 1837 was passed, not as the name might suggest but to indemnified British

Slave OWNERS for their loss! A total of

approximately 27.5 million dollars paid by the British tax payer, the final claim

by their descendant finalized in 2015.

** One of the world's oldest traded commodities, it is a sad fact that a market in human bondage for forced labor should still exist today. And, an awful indictment of humanity, that this extreme exploitation of our fellows should persist. Human trafficking, forced marriage, and tied labor is slavery by another name.

Sunday, September 19, 2021

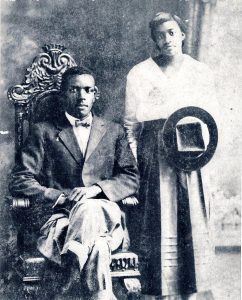

Lynching At The Courthouse: Lamar Smith Deserves A Courthouse Marker In Brookhaven

Please join this effort if you can. It’s important, and it’s time that we get this done. As the Daily Leader wrote last year, “Don’t ignore the past, even when it’s painful.”

Also read what Donna Ladd discovered about Lamar Smith murder, his murderers and other lynchings in Brookhaven, in her in-depth historic piece on his murder, “Buried Truth: Unresolved, Disregarded Lamar Smith Murder Haunts Lincoln County.“

Learn more about Lamar “Ditney” Smith in MFP Advisory Board member Keith Beauchamp’s documentary, “Murder in Black and White: Lamar Smith” and more about Emmett Till in “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till.“

Saturday, September 18, 2021

What happened on Highway 61: Part III: On Highway 90

Monday, September 6, 2021

What Happened on Highway 61 - Part 2: The Big Easy

Another most surprising and rewarding experience in New Orleans was that provided by the Ranger Service.

Saturday, August 14, 2021

What happened on Highway 61? - Part 1

A Blog Series by A. Tyke Dahnsarf

"Now I'm a man, way past twenty one, I tell you honey child, we gonna have lotsa fun."

--Bo Diddley (1955)

So, I finally made it. The trip I'd promised myself for decades; the Blues trail up the delta to see the birthplace and stomping grounds of the musical hero's that informed my youth.

Like the millions of ingratiate Baby-boomers raised in post war Britain, the land of hope and glory was not our sceptered Isle but country on the far side of the Atlantic. A place portrayed on 9 inch screens, in black and white. A tableau peopled by the square jawed and white, with teeth to match. Beneath wide-brimmed hats, they rode Palominos or running boards of Chevy's - able to discharge firearms with amazing accuracy, considering the speed that their chosen mode of transport often travelled. Females were portrayed as victims who screamed a lot and got rescued from precarious situations by the square jawed. Uncannily, their coiffures and make-up always survived the ordeal where their captors or protagonists often did not. In this safer real world, that our parents had bravely sacrificed their youth to make possible for us, there were no Colts, neither with 4 legs nor 6 chambers. Nor Stetsons, Borsellinos or Chevrolets. It was a world in reality, as Black and white as that projected onto screens or via a cathode ray tube.

So, we went further in embracing this perfect, mythic continent by imbibing it's music so that it became the soundtrack of our youth. Rock n' Roll was it's name and the more our parent's hated it so, we loved it the more. Then, when a home-grown, watered-down, insipid, mish-mash was offered once a week for an hour by Aunty Beeb (BBC TV) as a sop to the youth (and an establishment with an eye to future voters.) Some of us were audacious enough to seek out the itinerant father of Rock n' Roll - the Blues. Our parent's hated this even more. A number of those who had "discovered" this music also realized that the Devil had contrived to make it a musical genre (apparently) easy enough for whites to emulate. And so, some did just that, even I, but more of this later...

So, my informative years, like many in that post-World War II cohort, were first shaped by photogenic all American white boys--only just out of school--who regaled us with songs of love lost or gained. The most original and influential of them was one hailing from Texas and the other from Mississippi. With not a few ditties in their repertoire, a pastiche of songs from an all-together older generation, with very different life experiences, the raw immediacy of these ditties was not lost on us, even if the context of where and how they originated was.

One of these "oldies" was Chuck Berry, who along with perhaps Cliff Gallop launched a thousand guitar wannabes. Berry was not one to waste a good riff on one song when it could be applied to further telling of fast cars and even faster female. His witty couplets succeeded in making subsequent refinements somehow different, and I could not accuse Berry of lazy, moon in June lyrics in his telling of trysts with the opposite sex. I loved him then and still do. Keef, Mick, Eric et. al., also felt the same too. Along with adulating Messrs. Morganfield, Burnett, Hooker and many a King, they helped pave the way to resurrecting the careers of many these Black American Blues artists, catapulting them from cult following into the mainstream. But they were not solely responsible for my getting acquainted with Blues music. Nay! It was another champion, Chris Barber. A noted UK jazz band leader, it was he who first introduced me and thousands of others to these great performers, via TV--together with a Glaswegian banjo player and Parisian born guitarist, both members of Barbers band. The former with the moniker of Lonnie Donegan and the even more exotically named, Alexis Korner. Together they guided our musical journey and their example launched an untold number of Rhythm 'n Blues Bands.

The Denyms

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

Mt. Zion Memorial Fund with RL BOYCE PICNIC Presents Walk Like A Big Blues Mane Workshop Weekend w/ RL BOYCE

Plan to Get DUSTY in Como, MS

Oct. 16 & 17 2021

BOOGIE w / RL BOYCE Live

RL BOYCE, Living Hill Country Blues Legend gathered the best of Mississippi Blues players for his 2019 family picnic. Recorded live in Como, RL's newest release is 60 minutes of unfiltered, raw and rocking hypnotic electric Blues from North Mississippi A complication of astounding artists show-cases the wide range of unique sounds happening in Mississippi today. All players were inspired by the traditional music making methods RL BOYCE has employed for the last 50 years. Crowned King of the Hill Country Boogie RL BOYCE closes the disc with a transcendent jam that takes you HIGHER!

Come celebrate in person with the Big Blues Mane.

Grab yourself a copy at the RL BOYCE PICNIC Walk like A Big Blues Mane Workshop Weekend Oct. 16 & 17, 2021, Como MS. RL will have a mess of copies on hand, and ready to sign. CD ONLY limited release available on WoodB Records. Recorded SEPT. 1, 2019, RL BOYCE PICNIC, COMO, MS.

These recordings were made possible with generous support from the Mississippi Arts Commission.

Monday, August 9, 2021

The History of Race and Memorialization in the United States: Resources from the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund

“A Juneteenth Dilemma: Freedom and Self-Determination” by Channon Miller and T.J. Tallie (Perspectives on History, 2021)

“Erasing History or Making History? Race, Racism, and the American Memorial Landscape,” a Virtual AHA webinar featuring David W. Blight, Annette Gordon-Reed, and James Grossman (YouTube, 2020)

“A Monument to Black Resistance and Strength: Considering Washington, DC’s Emancipation Memorial” by Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove (Perspectives on History, 2020)

“Named for the Enemy: The US Army’s Confederate Problem” by Ty Seidule (Perspectives on History, 2020)

“Rumors of War Arrives in the South: Changes to Richmond’s Monumental Landscape” by Ryan K. Smith (Perspectives on History, 2020)

“Setting the Lost Cause on Fire: Protesters Target the United Daughters of the Confederacy Headquarters” by Karen L. Cox (Perspectives on History, 2020)

“Can We Right the Past? Memory and the Present” by Caroline E. Janney (AHA Today, 2018)

“Monumental Effort: Historians and the Creation of the National Monument to Reconstruction” by Kritika Agarwal (AHA Today, 2017)

“The Struggle to Commemorate Reconstruction” by Sarah Jones Weicksel (AHA Today, 2018)

“What Should We Do with Confederate Monuments?” by Dane Kennedy (AHA Today, 2017)

Monday, May 31, 2021

"They Say Drums was a-Calling": African-American Music from the Mississippi Hill Country

All Photos from the Alan Lomax Collection

|

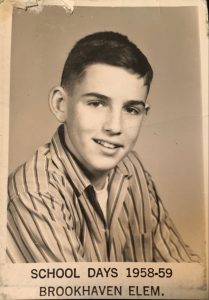

| Ed Young and Lonnie Young, 1959 |

|

Sid Hemphill, 1959 |

Friday, February 19, 2021

The Meaning of "Panther Burn"

- “The band’s name reflected the lore surrounding Panther Burn, Mississippi. This town was menaced by an elusive wild beast that, when finally cornered, was set aflame. Its dying shrieks so horrified the citizens that they named the community for it. The moniker was appropriate for” Tav Falco’s assembly of musicians, The Panther Burns.

|

(Jackson, MS) Clarion Ledger, Nov 1, 1987. On February 17, 2021, I posted a link to the above blog post on a Facebook post containing an interview with Tav Falco [click here for the interview], and I was fortunate enough to get a lengthy response from Mr. Falco himself, who not only took the time to correct a couple of grammatical errors in my post--namely that I hade misspelled Vicksburg as "Vickburg" as well as got the name of the newspaper incorrect; instead of the Herald, it was the Whig. Both have now been corrected in the above post. I find Mr. Falco's response both enlightening and informative; thus, I republish it here for your reading enjoyment! "Thank you for your comment. You have written, "It's not clear at all where this supposed lore came from--perhaps the mind of Falco himself, or Gordon's own exaggeration--but the town of Panther Burn has plenty of actual historical information related to the naming of the town. Here is one news item from the Vickburg Herald in 1860 that explains how the town got its name." One might wonder how many panthers in Mississippi were shot down, trapped, maimed, or burned alive inadvertently or otherwise. I should imagine lots of them, esp. during the times when the wilderness was being cleared for cultivation of crops. Murdered and destroyed along with legions of other august creatures such as bear (Mr. Faulkner attested to that), bobcats, wild boar, foxes, and so on. That item Mr. Moore has cited appears to be from the Oxford Intelligencer 1860, yet it is credited to the Vickburg (does he intend VickSburg?) Herald 1860, while that newspaper did not begin publishing until 1897. Was this item a reprint 37 years later? Anyway, the point is that among the endless slayings of grand creatures of the wild, this instance of the slaughter of the 'treed varmint' may not have even been reported - as I suspect most were not - had the hunter not been a so-called "gentleman" who removed the paw of the animal and had taken it to a doctor's office for the public to view as the veracity of his claimed exploit. Does this newspaper item account for anything more than panthers were killed in the area? This paragraph by Nick Nicholas, PhD in Linguistics from Melbourne University appears relevant to the topic: "The English equivalent of “burn” in Scots/Scottish-English isn’t “burn” in the sense of “be consumed/damaged by fire”, it is “bourne” which has pretty much the same meaning of “stream” and is found in lots of place names like “Bournemouth” or “Holborn” in London. Both come from Anglo-Saxon, the ancestor language of both Scots and English, so it’s not that there has been a change in meaning, more that the term has survived in Scots and Scottish English, but fallen out of use in England, except where it has been fossilized in names." So, we could surmise that in the Scottish dialect supposedly spoken around the Panther Burn area, the term 'burn' may - by a stretch - have described "swampy" conditions as alluded to in the note the Jackson, MS Clarion Ledger published in 1987. Swampy because many 'streams' in Mississippi are not flowing streams at all, rather they are swamps of brackish water. If one happens to read my book, Ghosts Behind The Sun: Splendor, Enigma, and Death, there it is written how Tav Falco learned of the Panther Burn legend. A Memphis musician, the late Sid Selvidge, had been reared - so to speak - in the planter society of Greenville 34 miles distant from the community of Panther Burn. It was he who had related the legend to Falco to satisfy his curiosity. Mr. Moore is right in that 'it is not clear at all where this supposed lore came from.' Yet we have a reality that is irrefutable. We have the reality of a legend. As legend where concrete historical dates, names, and charters can only be implied, inferred or imagined. A reality that will forever remain a mystery and as such a legacy for which we can be grateful. Are we too eager to assault our minds and lives with purported historical facts, figures, and statistics in our quest to gleefully proclaim fiction over fact? What is passed on by word of mouth and escapes the scrutiny of microscopic, analytical, methodical, deconstructive interrogation, might be that ineffable, elusive "rara materia" from which poetry, music, and art are created. When spoken stories do become legend, they become larger than life. One might howl: superstition! shadowy Romanticism! Well, yes. There are particles of these in all tales and legends. Yet legends loom larger than textbooks. We must approach legends on their own terms for they are larger than we are. We can perversely try to pick them apart and to deflate them, but they will always return. They will return because, in the end, you find that legends are drawn from fact however obscure; otherwise they would not exist. Nor would their supra-reality be one that lives and breathes across time, fashion, class, and culture. The choice is ours. We can disregard legend, allow ourselves to be oppressed by it, or to be imaginatively stimulated, or allow ourselves to be inspired by it, or to charge off in all directions trying to live out legends. One thing is for sure. Legends loom larger than FATE itself. As a final aside, the Memphis (b. Earle, Arkansas) artist, Carroll Cloar, entitled his painting on the legend as "Panther Bourne." |

-

B.B. King at Dockery Farms in the 1970s In their “Response” (vol. 50, no. 1, Spring 2019) to T. DeWayne Moore’s article “Revisiti...

-

A Blog Series by A. Tyke Dahnsarf "Now I'm a man, way past twenty one, I tell you honey child, we gonna have lotsa fun." --Bo ...

-

by Arne Brogger, organizer and road manager of the Memphis Blues Caravan in the 1970s, ( blog post, " The Straight Oil From The Can: T...

-

The [Memphis Country] Blues Festival [was] an occasion unto itself, quite unlike any other. The aging troubadours of the first truly ...

-

In 1972, McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters, won his first Grammy Award, for Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording for They Call Me Mu...